Body

Rupture and repair––Crafts Magazine Issue #298: Spring/Summer 2024

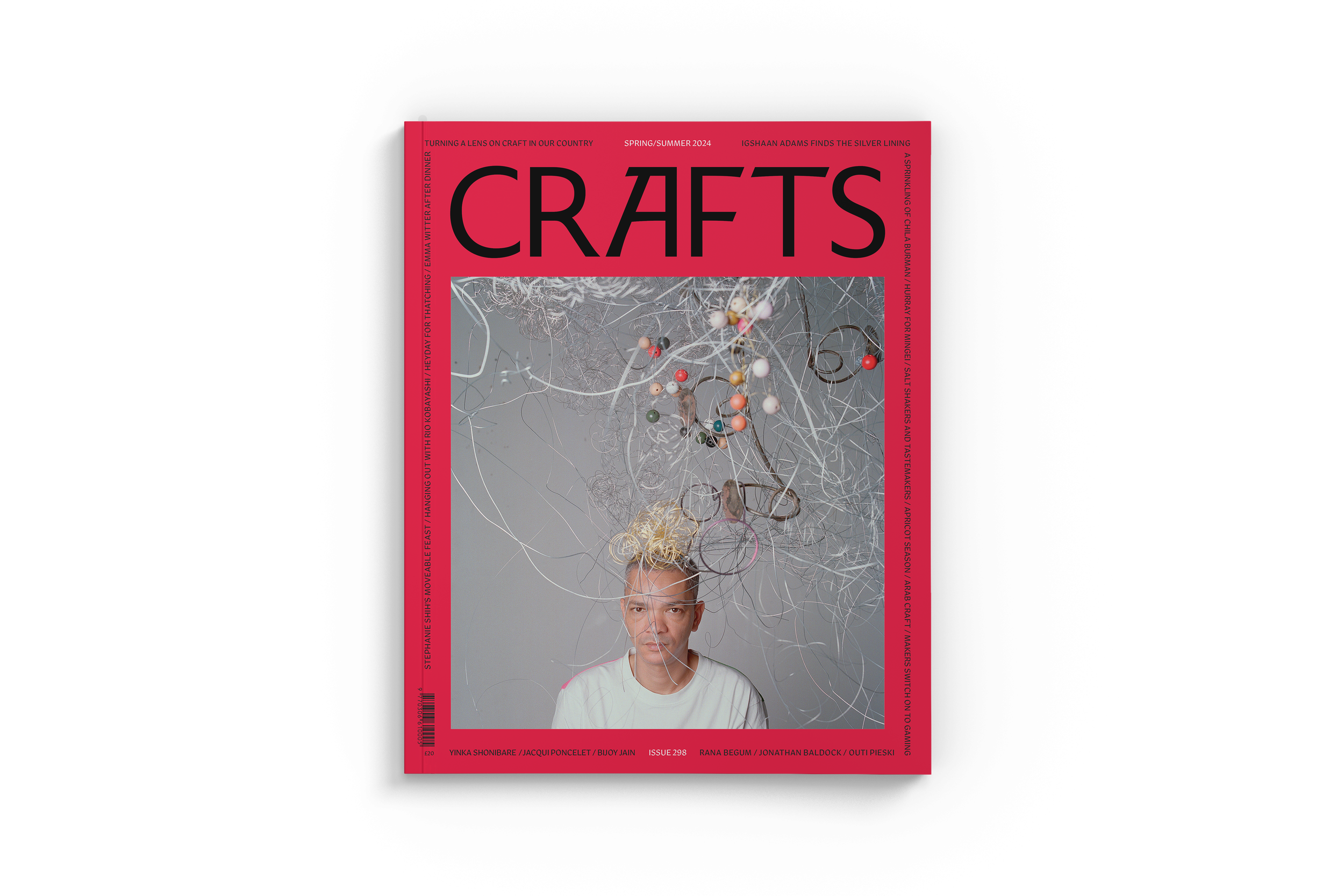

Crafts Magazine – Issue #298

"The Arab world is a diverse region, shaped by a fusion of cultures, traditions, histories and beliefs. The great cities of the past – Damascus, Beirut, Tripoli and the coastal cities in Palestine – were hotbeds for textile production, weaving, embroidery and various wood crafts. Being well connected by sea to southern Europe, Turkey and Persia, these cities made products that travelled far; their intricate details desired as symbols of opulence and status.

This long tradition of craft and connectivity in trade is still seen in contemporary Levantine craft and design today, which I captured while curating Arab Design Now, an exhibition at the inaugural biennial Design Doha looking at commonalities.

in contemporary design from the Levant, the Gulf and North Africa. Among the 74 exhibitors from across the Arab world are designers who not only spread their crafts around the globe, but expand and blend their design approaches with others, from Europe to Japan, taking them in new directions altogether. These practices include Beirut-based Studio Nada Debs, who adds a new dimension to working with mother-of-pearl inlay, and Lebanese- Polish architects Tessa and Tara Sakhi, who exchange knowledge with Murano glassblowers.

What’s also clear is that the upheavals of the 20th and 21st centuries, in the form of wars, revolutions and conflicts, have created massive ruptures. These cataclysmic moments have disconnected us from our roots, carved deep rifts between past and present and redefined our relationship to the land and to each other. Many contemporary designers practising in the region have embarked on a reconciliatory act to heal these ruptures, rediscovering heritage- based traditions and rituals, with an eagerness to reinterpret and evolve them.

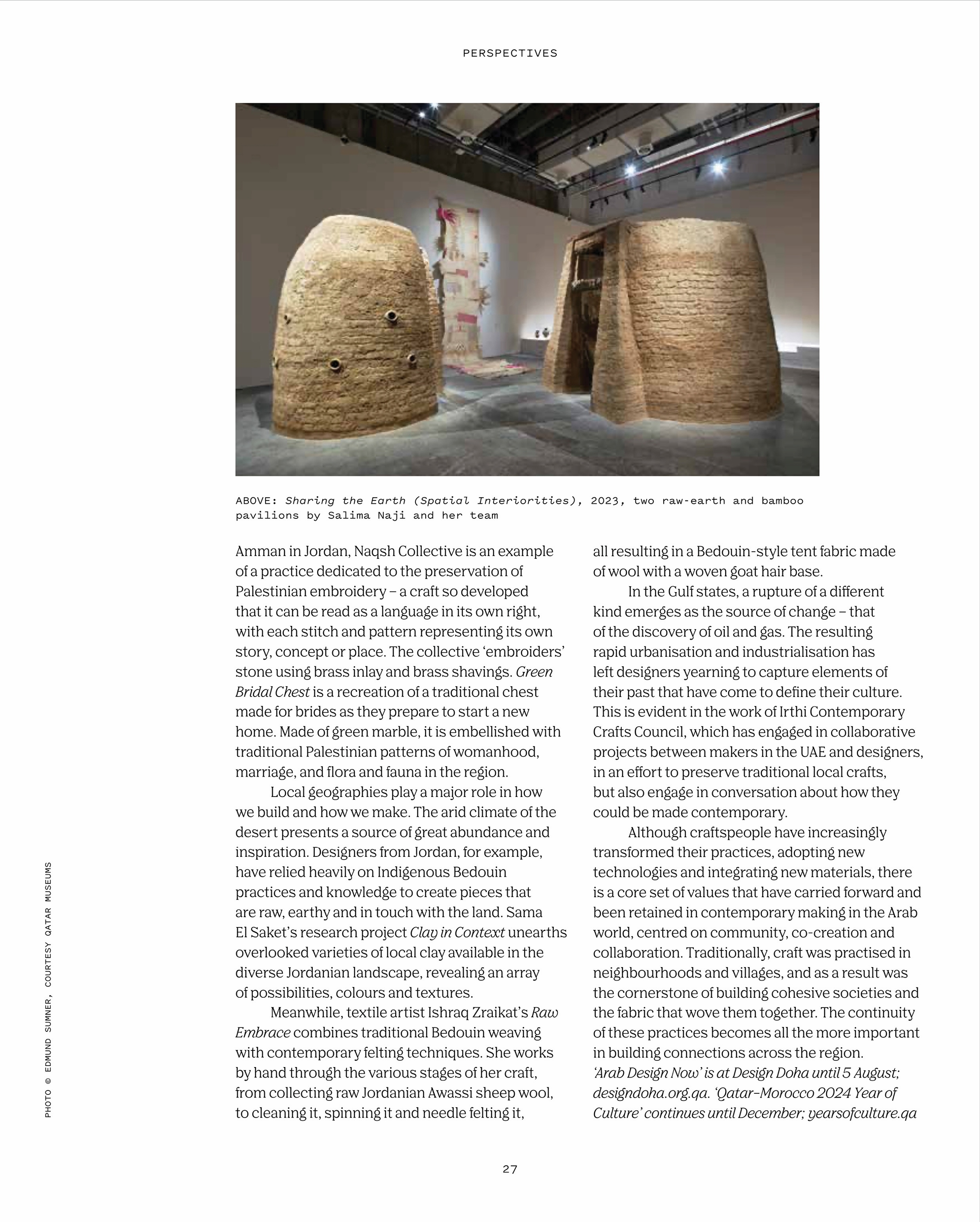

As a survey exhibition, Arab Design Now presented the conversation about craft in the Arab world as an extension of the land. The commission of two raw-earth and bamboo pavilions by anthropologist Salima Naji and her team of three ma’almeen (master artisans) in Morocco was intended to shift the conversation away from consumerist or urban understandings of ‘contemporary’ and more towards the often- overlooked folk crafts that continue to be practised in rural settings. The boat carrying materials for the pavilions – raw clay, adobe, bamboo, jrid and aqarnif palm, lovingly harvested and created by Naji – never made it to Doha in time, due to the violence erupting in Gaza, and a few Yemeni men disrupting the entire global shipping order in response.

In search of an alternative, we learned of Torba Farm in Qatar, an immense oasis sculpted and seeded by Mohammad Al-Khater. In an unexpected exchange between Moroccan craftsmen and Qatari makers, all the materials needed for the creation of her two pavilions were sourced and crafted on site, and a collaboration was born. The experience lays testimony to the commonalities that run from North Africa to the Arabian Gulf. Design and craft from the Arab world is, first and foremost, characterised by a deep love and understanding of the land, and a sensitivity to the materials and possibilities that it yields. In Palestine, such a continuity of exchange is not possible, however, as the 75-year political and economic occupation of its land has curtailed the trade of crafts. In such a context of intentional erasure and violence, efforts to preserve and continue craft become more pressing. Based in Amman in Jordan, Naqsh Collective is an example of a practice dedicated to the preservation of Palestinian embroidery – a craft so developed that it can be read as a language in its own right, with each stitch and pattern representing its own story, concept or place. The collective ‘embroiders’ stone using brass inlay and brass shavings. Green Bridal Chest is a recreation of a traditional chest made for brides as they prepare to start a new home. Made of green marble, it is embellished with traditional Palestinian patterns of womanhood, marriage, and flora and fauna in the region.

Sharing the Earth (Spatial Interiorities), 2024 — Salima Naji. Arab Design Now - Doha Design Biennale 2024.

Local geographies play a major role in how we build and how we make. The arid climate of the desert presents a source of great abundance and inspiration. Designers from Jordan, for example, have relied heavily on Indigenous Bedouin practices and knowledge to create pieces that are raw, earthy and in touch with the land. Sama El Saket’s research project Clay in Context unearths overlooked varieties of local clay available in the diverse Jordanian landscape, revealing an array of possibilities, colours and textures.

Meanwhile, textile artist Ishraq Zraikat’s Raw Embrace combines traditional Bedouin weaving with contemporary felting techniques. She works by hand through the various stages of her craft, from collecting raw Jordanian Awassi sheep wool, to cleaning it, spinning it and needle felting it,

all resulting in a Bedouin-style tent fabric made of wool with a woven goat hair base.

In the Gulf states, a rupture of a different kind emerges as the source of change – that of the discovery of oil and gas. The resulting rapid urbanisation and industrialisation has left designers yearning to capture elements of their past that have come to define their culture. This is evident in the work of Irthi Contemporary Crafts Council, which has engaged in collaborative projects between makers in the UAE and designers, in an effort to preserve traditional local crafts, but also engage in conversation about how they could be made contemporary.

Although craftspeople have increasingly transformed their practices, adopting new technologies and integrating new materials, there is a core set of values that have carried forward and been retained in contemporary making in the Arab world, centred on community, co-creation and collaboration. Traditionally, craft was practised in neighbourhoods and villages, and as a result was the cornerstone of building cohesive societies and the fabric that wove them together. The continuity of these practices becomes all the more important in building connections across the region."